The latest readings from the “bubble indicator.”

As you know, I like to convert my intuitive thinking into indicators which I write down as decision rules (principles) that can be back-tested and automated to put together with other principles and bets created the same way to make up a portfolio of alpha bets. I have one of these for bubbles. Having been through many bubbles over my 50+ years of investing, about 10 years ago I described what in my mind makes a bubble and use that to identify them in markets—all markets, not just stocks.

Q1 2022 hedge fund letters, conferences and more

I define a bubble market as one that has a combination of the following in high degrees:

- High prices relative to traditional measures of value (e.g., by taking the present value of their cash flows for the duration of the asset and comparing it with their interest rates).

- Unsustainable conditions (e.g., extrapolating past revenue and earnings growth rates late in the cycle when capacity limits mean that that growth can’t be sustained).

- Many new and naïve buyers who were attracted in because the market has gone up a lot so it’s perceived as a hot market.

- Broad bullish sentiment.

- A high percentage of purchases being financed by debt.

- A lot of forward and speculative purchases made to bet on price gains (e.g., inventories that are more than needed, contracted forward purchases, etc.).

I apply these criteria to all markets to see if they’re in bubbles. I have periodically shown you these for stocks and the stock market.

What Was Shown in January and What Is Shown Now

I will first describe in words and then will show in charts the picture and how it has changed since January, when I last shared an update of the bubble indicator.

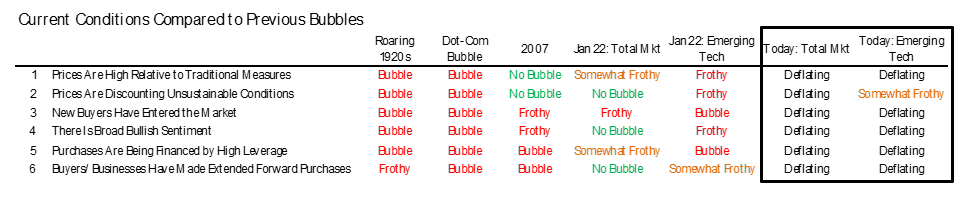

In January the bubble indicator showed that a) the US equity market as a whole was at the edge of a bubble but not in an extreme bubble (i.e., 70% of the way toward the highest bubble, which happened in late 1990s and late 1920s) and b) the emerging tech companies (e.g., Tesla and Roku) were clearly in an extreme bubble. I also noted that other bubbly behavior (e.g., SPACs, the IPO boom, the big pickup in options activity) financed by the unprecedented flood of liquidity post-COVID had found its way into the asset markets, making things bubbly. I showed which stocks were in bubbles and created an index of those stocks, which I call “bubble stocks.”

Since then, those bubble stocks popped. They declined by about a third over the last year—while the S&P 500 is about flat. With those and other developments in the market—e.g., meaningful decline in frothy retail activity, meaningful deterioration in sentiment, and more—the emerging tech stocks no longer appear to be in a bubble, but neither do they appear to have substantially swung to the opposite extreme, so it’s not necessarily true that now is a good time to buy them.

Bubbles can take a long time to unwind (two years in the case of the 1929 bubble, one year in the case of the late ’90s tech bubble) and typically go to the opposite extreme, so just because they aren’t at a bubble extreme doesn’t mean they are safe or that it’s a good time to get long. In fact, US stocks in aggregate still look overvalued by our measures. History shows that once the popping begins, bubbles more often overcorrect to the downside versus settling at more “normal” prices.

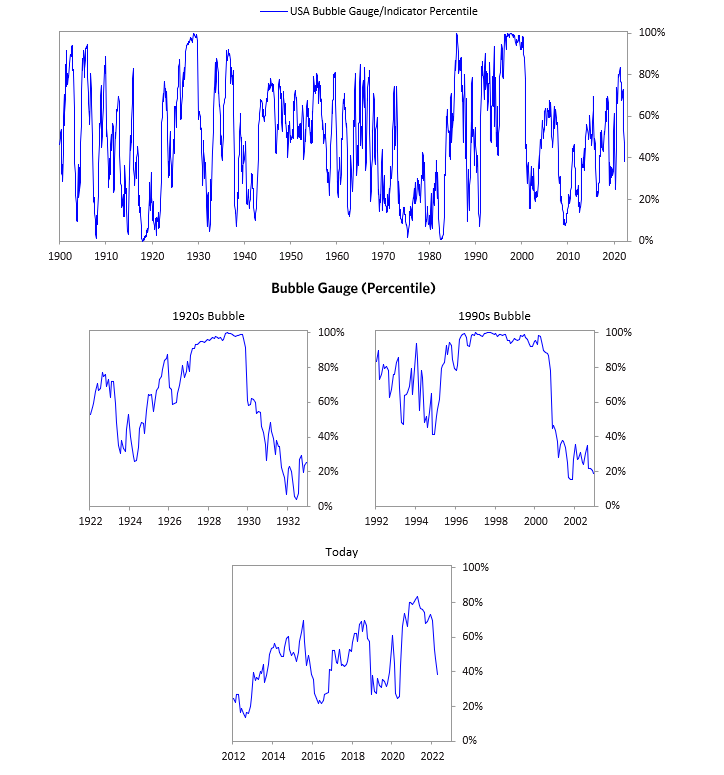

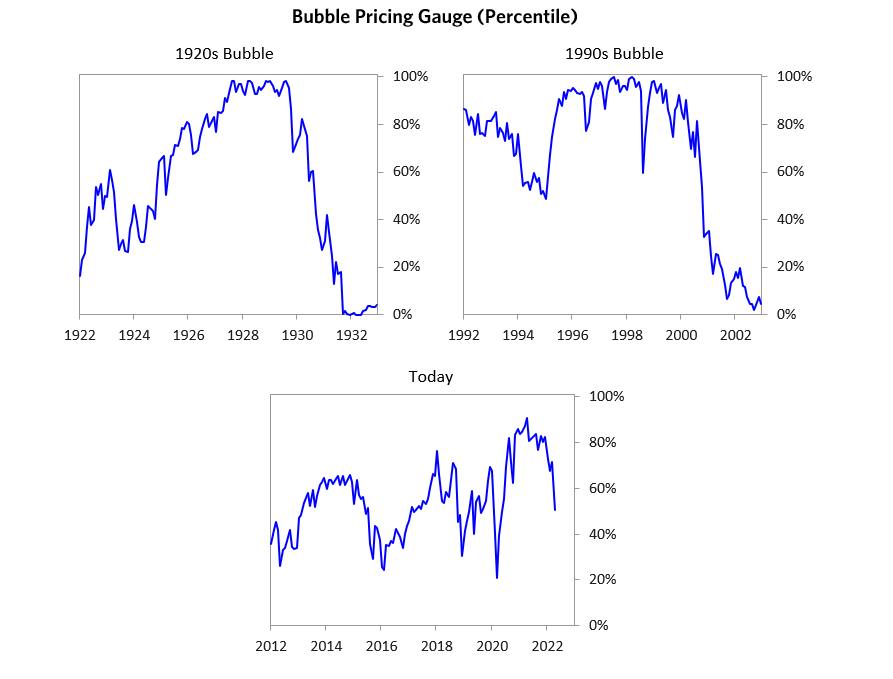

The following charts paint the picture. The first shows the bubble gauge/indicator going back to 1900 for the US equity market as a whole—currently at the 40th percentile. The charts also zoom in on the gauge over the last couple of years, along with the late 1920s bubble and the late 1990s bubble (during both of these cases the gauge reached 100%).

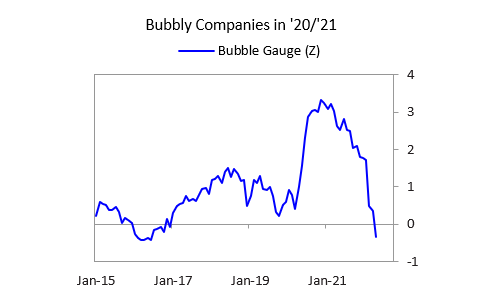

The chart below shows the bubble gauge for the average of the most bubbly companies as defined in 2020. Readings for those companies are meaningfully down.

The charts below show the performance of a basket of emerging tech bubble stocks (what we call the “bubble slice”) versus the S&P 500. Prices have meaningfully declined and have given up most of their post-COVID gains.

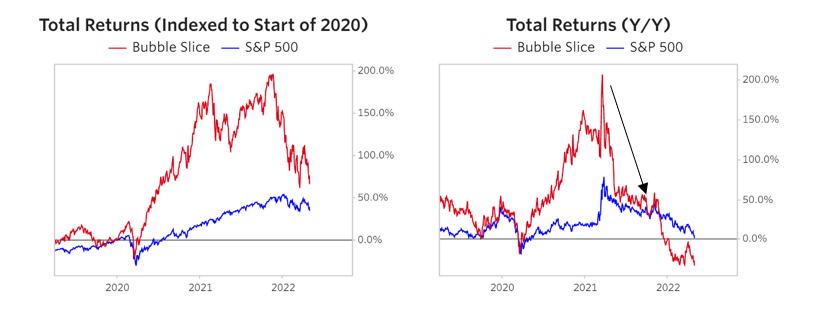

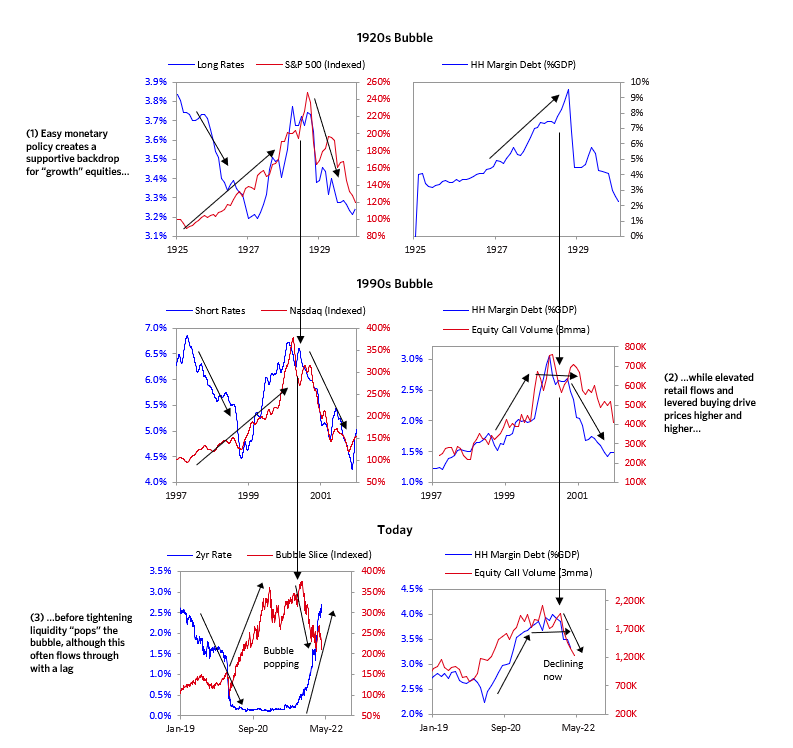

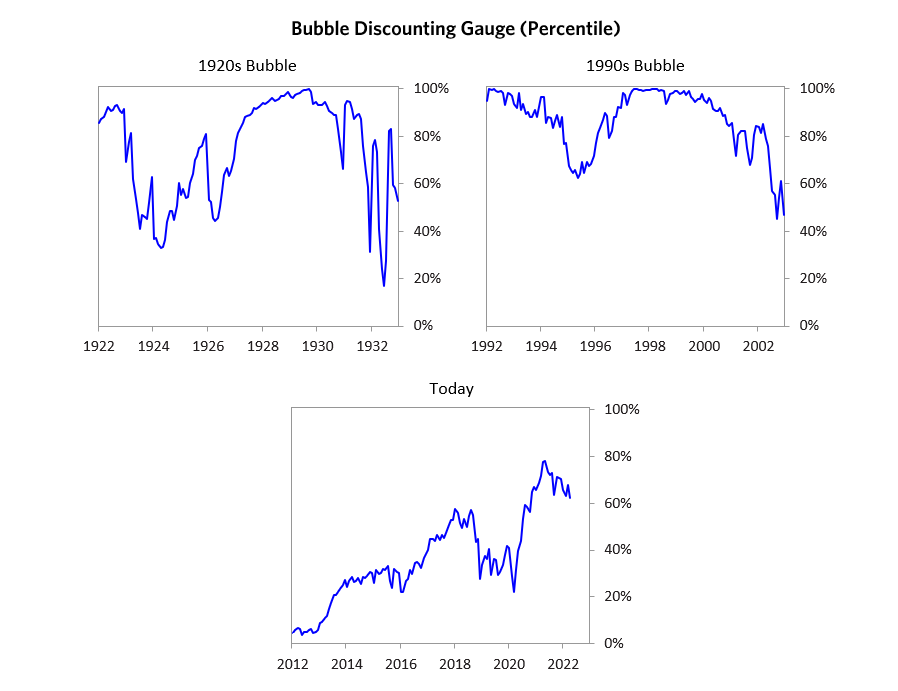

The following charts show the price action of the bubble slice today and in the two biggest bubbles—in the 1920s and 1990s. In these charts, you can see the analogous market dynamic, along with two of the key indicators. While these are only two of several indicators, they show how a lot of debt financing stock ownership together with a tightening typically leads to the popping of the bubble.

Everything we’re seeing driving the bubbles in this segment of the market is classic—virtually the same drivers we saw 100 years ago in the 1920s and a little over 20 years ago in the 1990s bubble. For instance, in the last couple months, it was how tightening can act to prick the bubble. To understand these dynamics, you might want to review this case study of the 1920s stock bubble (starting on page 49), from my book Principles for Navigating Big Debt Crises.

The following charts walk through each of the pieces of the bubble gauge for the US stock market as a whole. While I won’t show you exactly how this indicator is constructed because that is proprietary, I will show you some of the sub-aggregate readings and some indicators.

Each of these six influences is measured using a number of stats that are combined into gauges. In the stock market, this approach is applied each stock that I’m looking at. These gauges are combined into aggregate indices by security and then for the market as a whole. The table below shows the current readings of each of these gauges for the US equity market. It shows how the conditions stack up today for US equities in relation to past times. These readings suggest that we’re out of a bubble.

-

How High Are Prices Relative to Traditional Measures?

The current read on this price gauge for US equities is around the 50th percentile.

-

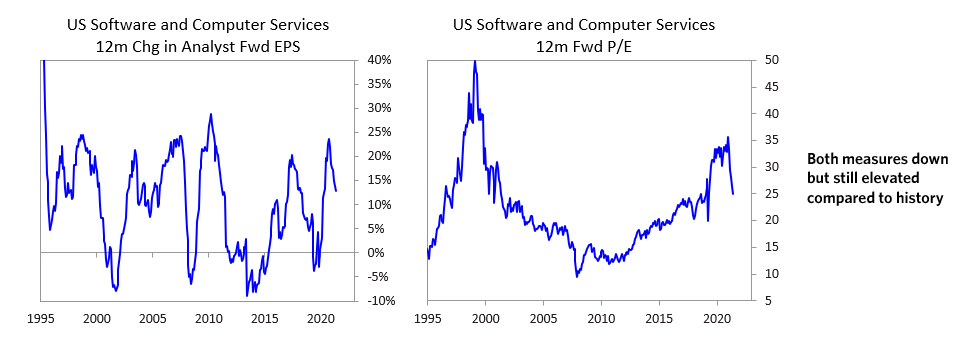

Are Prices Discounting Unsustainable Conditions?

This measure calculates the earnings growth rate that is required to produce equity returns in excess of bond returns. This is derived by looking at individual securities and adding up their readings. Currently, this indicator is just around the 60th percentile for the aggregate market—more elevated than some of our other readings. The earnings growth discounted in stocks is still a bit high.

This is even more noticeable in the US software sector. Analyst earnings growth expectations for this sector have come down, but they are still relatively high compared to history. P/Es have reversed their COVID gains, but remain high compared to history.

-

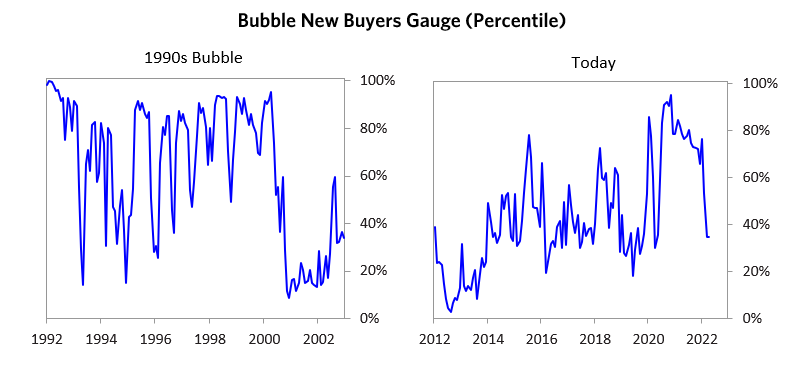

How Many New Buyers (i.e., Those Who Weren’t Previously in the Market) Have Entered the Market?

A rush of new entrants attracted by rising prices is often indicative of a bubble. This was the case in the 1990s equity bubble and in the 1929 bubble, based on accounts of the time (though, regrettably, our data doesn’t go back that far for this gauge and some of the gauges we’ll show next). This gauge shot above the 90th percentile in 2020 due to the flood of new retail investors into the most popular stocks, which by other measures appeared to be in a bubble. More recently, we have seen meaningful moderation in the pace of retail activity in the markets—it’s now back around pre-COVID averages.

-

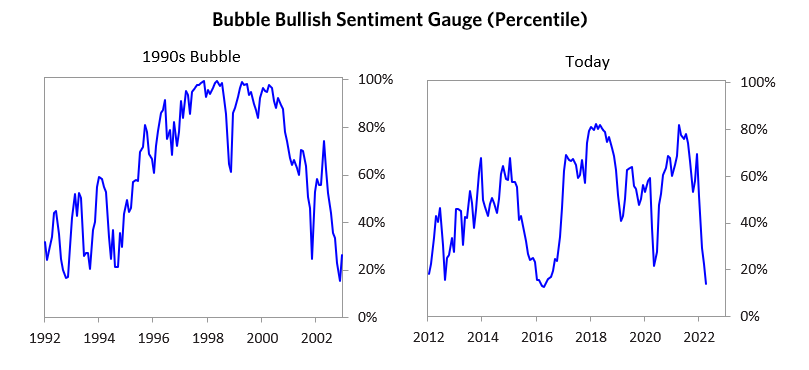

How Broadly Bullish Is Sentiment?

The more bullish the sentiment, the more people have already invested, so they are likely to have fewer resources to keep investing and are more likely to sell. Sentiment in the market is now significantly negative.

-

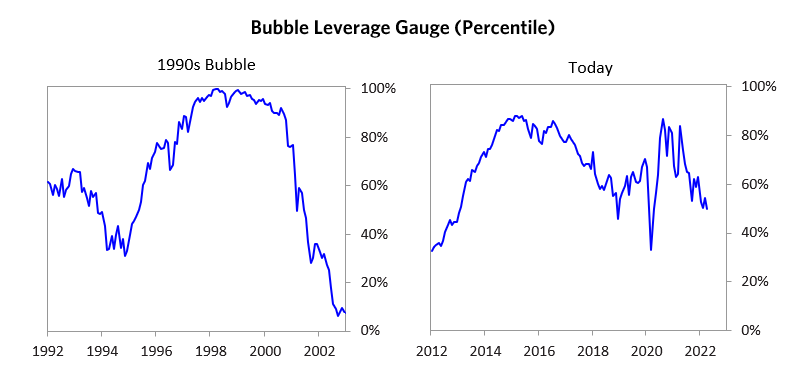

Are Purchases Being Financed by High Leverage?

Leveraged purchases make the underpinnings of the buying weaker and more vulnerable to forced selling in a downturn. The leverage gauge, which looks at the leverage dynamics across all the key players and treats option positions as a form of leverage, is now showing a read around the 50th percentile.

-

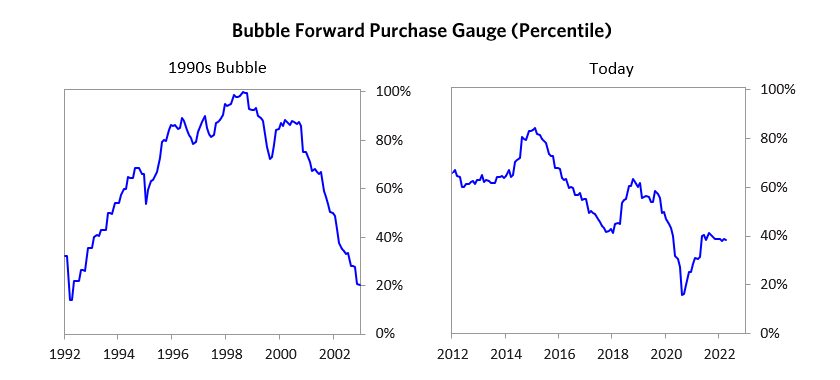

To What Extent Have Buyers Made Exceptionally Extended Forward Purchases?

One perspective on whether expectations have become overly optimistic comes from looking at forward purchases. I apply this gauge to all markets and find it particularly helpful in commodity and real estate markets, where forward purchases are most clear. In the equity markets, I look at indicators like capital expenditure—whether businesses (and, to a lesser extent, the government) are investing a lot or a little in infrastructure, factories, etc. It reflects whether businesses are extrapolating current demand into strong demand growth going forward. This gauge is at the 40th percentile, similar to other gauges.

What one chooses to do with this is a tactical decision. While the reversal has been significant, discounting of future earnings remains somewhat high compared to history. And either way, bubbles more often overcorrect (sell off more than the fundamentals would suggest) versus just settling back to normal levels. But I wanted to pass along these updated readings to you in light of what’s now going on in the markets.

Bridgewater Daily Observations is prepared by and is the property of Bridgewater Associates, LP and is circulated for informational and educational purposes only. There is no consideration given to the specific investment needs, objectives or tolerances of any of the recipients. Additionally, Bridgewater's actual investment positions may, and often will, vary from its conclusions discussed herein based on any number of factors, such as client investment restrictions, portfolio rebalancing and transactions costs, among others. Recipients should consult their own advisors, including tax advisors, before making any investment decision. This report is not an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to buy the securities or other instruments mentioned.

Bridgewater research utilizes data and information from public, private and internal sources, including data from actual Bridgewater trades. Sources include, the Australian Bureau of Statistics, Bloomberg Finance L.P., Capital Economics, CBRE, Inc., CEIC Data Company Ltd., Clarus Financial Technology, Conference Board of Canada, Consensus Economics Inc., Corelogic, Inc., CoStar Realty Information, Inc., CreditSights, Inc., Credit Market Analysis Ltd., Dealogic LLC, DTCC Data Repository (U.S.), LLC, Ecoanalitica, Energy Aspects, EPFR Global, Eurasia Group Ltd., European Money Markets Institute – EMMI, Evercore, Factset Research Systems, Inc., The Financial Times Limited, GaveKal Research Ltd., Global Financial Data, Inc., Harvard Business Review, Haver Analytics, Inc., The Investment Funds Institute of Canada, ICE Data Derivatives UK Limited, IHS Markit, Impact-Cubed, Institutional Shareholder Services, Informa (EPFR), Investment Company Institute, International Energy Agency (IEA), Investment Management Association, JP Morgan, Lipper Financial, Mergent, Inc., Metals Focus Ltd, Moody’s Analytics, Inc., MSCI, Inc., National Bureau of Economic Research, Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OCED), Pensions & Investments Research Center, Qontigo GmbH, Quandl, Refinitiv RP Data Ltd, Rystad Energy, Inc., S&P Global Market Intelligence Inc., Sentix GmbH, Spears & Associates, Inc., State Street Bank and Trust Company, Sustainalytics, Totem Macro, United Nations, US Department of Commerce, Verisk-Maplecroft, Vigeo-Eiris (V.E), Wind Information(HK) Company, Wood Mackenzie Limited, World Bureau of Metal Statistics, and World Economic Forum. While we consider information from external sources to be reliable, we do not assume responsibility for its accuracy.

The views expressed herein are solely those of Bridgewater as of the date of this report and are subject to change without notice. Bridgewater may have a significant financial interest in one or more of the positions and/or securities or derivatives discussed. Those responsible for preparing this report receive compensation based upon various factors, including, among other things, the quality of their work and firm revenues.

Article by Ray Dalio via LinkedIn