My first trip to the Berkshire Hathaway (NYSE:BRK.A) (NYSE:BRK.B) annual meeting in Omaha was over 20 years ago, in 2002. I was a rookie analyst at Fidelity Investments, and the firm sent a whole contingent of analysts and portfolio managers for the annual pilgrimage. It was quite an initiation into the cult of Warren Buffett.

The size of the gathering was quite modest by today’s standards, a “mere” 10,000 attendees. Working for one of the largest investment firms had its perks – Morgan Stanley hosted a dinner with Warren the night before the meeting for its most important clients, and I got the chance to ask him a question in a somewhat more intimate setting of only about 200 people.

I was star-struck. I had read everything that I could get my hands on by or about Buffett prior to coming to Omaha. In fact, I owe my investment career in part to him – it was listening to him speak on campus at MIT’s Sloan School of Management circa 2000 that turned me on to value investing in the first place.

At the Morgan Stanley dinner, I asked Warren what he looks for in a company that he is considering as a potential investment for the first time. I am sure that it was a question he had faced many times, but he was very gracious and didn’t let on.

He patiently explained that the first thing he thinks about is whether he can approximately estimate the key economic variables for the business 10+ years out. If he can’t, he passes right away. That simple litmus test saved me a lot of trouble over my subsequent 20+ years of professional value investing.

I have gone to the Berkshire Hathaway annual meeting a total of 10 times. I continued to read everything that I could by Buffett. I admire him and his accomplishments, and have learned a tremendous amount from what he has said and written. I have even written an article about Warren Buffett’s evolution as an investor.

But I have left the Cult of Warren Buffett. I admire the man, I have learned a lot from him, but I would rather think for myself.

A cult? In Cultish by Amanda Montell the author points out that all cults, despite their differences share certain characteristics. A cult-specific language. A charismatic leader. Shared beliefs about the world. A community of cult members who create an echo-chamber of support and reinforcement of the cult’s beliefs.

Buffett’s is a happy cult. We need not fear any crazy behavior or drinking from some poisoned chalice. Yet it fits the criteria of a cult quite well.

Over my 20+ years of investing I have met many young Buffett acolytes blindly quoting the great man’s investing wisdom without fully understanding it. Professional investors running around calling themselves Warren Buffett “cloners.”

Groupies who attempt to gain social status within the cult by posting copies of thank-you notes from Warren or better yet a snapshot of them together on social media.

Those strivers attempting even higher position in the cult pecking order might post a picture at some exclusive event or dinner to show others how much closer they are to the Leader than mere rank-and-file cult members.

Isn’t it ironic? The man who accomplished so much via independent, first-principles thinking is celebrated by blind adulation and imitation. After all, in the Warren Buffett Cult things are true or not based on whether the great leader has said them. His words are truth to his followers.

You don’t see Warren Buffett running around blindly quoting Benjamin Graham, right? Otherwise Buffett’s success would have been but a pale shadow of what he has accomplished.

No – he learns from others but thinks for himself. Yet somehow rather than internalize that truth the cult members are happy enough just quoting him and repeating his favorite phrases. I suspect it’s easier that way. I also suspect it’s not exactly a path to outsized investment success.

Let me give you an example. One of the most well-worn Buffett-ism is: “I would rather buy a great business at a fair price than a fair business at a great price.” If only I had a dollar for every time I have seen this posted somewhere or used to justify paying a high price for a good company.

That’s what Buffett says in public. Think about it – he is trying to position himself to buy businesses in the future from business owners whom he wants to stay on as managers. The cold truth of his value proposition to them is this: you get less money for your business than you would in an auction, but you will be happier about it because it will have a permanent home and I won’t fire your employees.

Warren is very polished and understands human nature. After all, are people more likely to sell to him at a below-market price if he keeps repeating the “great business at a fair price” mantra or if he makes it explicit that he is getting their business on the cheap?

Someone once told me that when asked about this quote in private he replied something along the lines that no, he wants to buy businesses at a crazy bargain-level price. Regardless, we don’t need any special sources because we can see what Buffett actually does with Berkshire Hathaway’s cash.

He has tens of billions of excess capital. He knows plenty of great businesses. They have traded at “fair,” whatever that means, prices over the years. He hasn’t bought them. Why? He is waiting for bargains that promise high rates of return. And paying “fair” prices for businesses doesn’t accomplish that on average. It’s that simple.

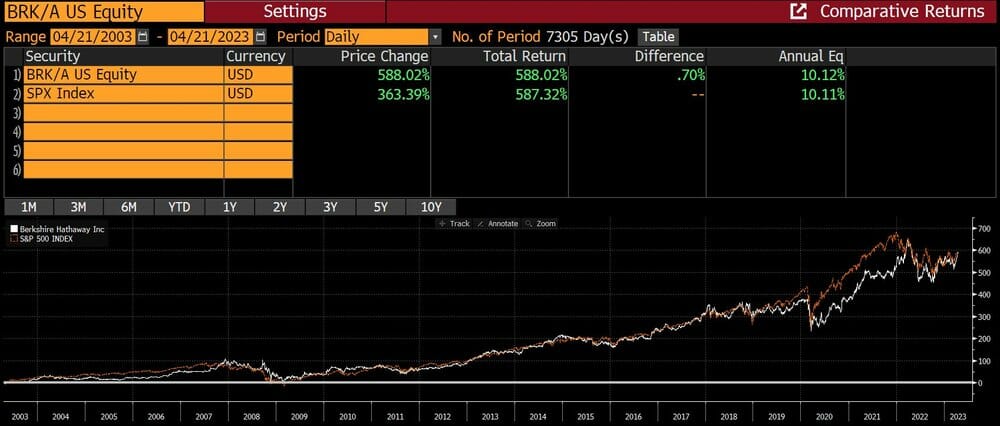

Speaking of returns. I happened to pull up Berkshire’s 20 year stock performance as compared to the S&P 500. Here is what I found:

A few things stood out:

- Berkshire’s total return is almost identical to the market over 20 years

- This period includes at least two market/economic cycles

- The 10% annual return achieved by the market during this period is consistent with the average of the last century

- Not that it should matter, but to the untrained eye Berkshire’s stock has had declines during the major market sell-offs that weren’t too different from the market’s

- The “buts” some might raise with these facts aren’t likely to be material enough to affect the main conclusion

What is that conclusion? Why hasn’t Berkshire done better than the market over the last two decades? I don’t know, but I suspect it’s some combination of:

- Size kills excess returns, and Berkshire’s size is a huge disadvantage

- The market’s returns have been concentrated in a small group of big winners of the kind that Buffett is unlikely to invest in because they don’t pass his “what will this business look like in 10 years” test for him

None of this is to imply that Buffett has lost his touch or isn’t great. He hasn’t and he is. He would likely crush almost everyone if he were managing $100M in capital. It would be fascinating to know what he would do with that sum. He will never tell us – at the 2023 Berkshire Hathaway meeting in a couple of weeks he will mostly repeat the same broad insights that he has shared countless times before.

There are many people who go to the Berkshire Hathaway annual meeting who aren’t cult members. Nor do they go because they think they will get some life-changing investment insight. They go for the atmosphere. Or to connect with friends. Or to get a sense of community, affirmation and support for a long-term investment process.

There are also many cult members who proudly admit to being in a cult, most only half-jokingly. After all, as I wrote earlier, it’s a happy cult.

Let’s be honest – it’s unlikely that any of us will approach the greatness that Buffett has achieved in his investment career. There is nothing wrong with giving credit where it’s due and admiring the man and his accomplishments. Or eating a Dilly Bar at the annual meeting for $1 that goes to charity while listening to comfortable sermons from the podium. Heck, I have done that myself more than a few times.

Let’s go back to where we started – my first Berkshire Hathaway annual meeting in 2002. As the youngest member of the Fidelity delegation, I was tasked with getting in line extra early so that the portfolio managers could get their beauty rest and still get good seats.

Eager to please, I was one of the first few dozen in line and saved the spot for the rest of our group. The crowd behind us was composed of well-dressed people of mild manners and somewhat advanced age. That is until the doors opened.

At that point, the line of these previously mild-mannered Berkshire millionaires collapsed into a surging mob with everyone rushing for the doors at once. Faced with the choice of physically blocking retirees from cutting me in line and letting it go, I chose the latter. The cult members would not be denied their chance to bask in their Leader’s glow, no matter the price.

If you are interested in learning more about the investment process at Silver Ring Value Partners, you can request an Owner’s Manual here.

If you like this article, please share it and subscribe to the free Behavioral Value Investor Substack where I write weekly articles on Investing and Behavioral Finance.

Note: This article originally appeared on the Behavioral Value Investor Substack